Talk about this project at local Python event

James was meant to give a talk at a local Python event in September. Unfortunately at the last minute the sponsor, venue and event fell through. Instead of wasting the talk we'll post it here (as we were going to do afterwards anyway). Hopefully it's not our fault the event had problems!

EDIT: This talk was later given at Glasgow Python on 7th May 2025 instead - thanks!

Hello, I want to start by showing you some websites.

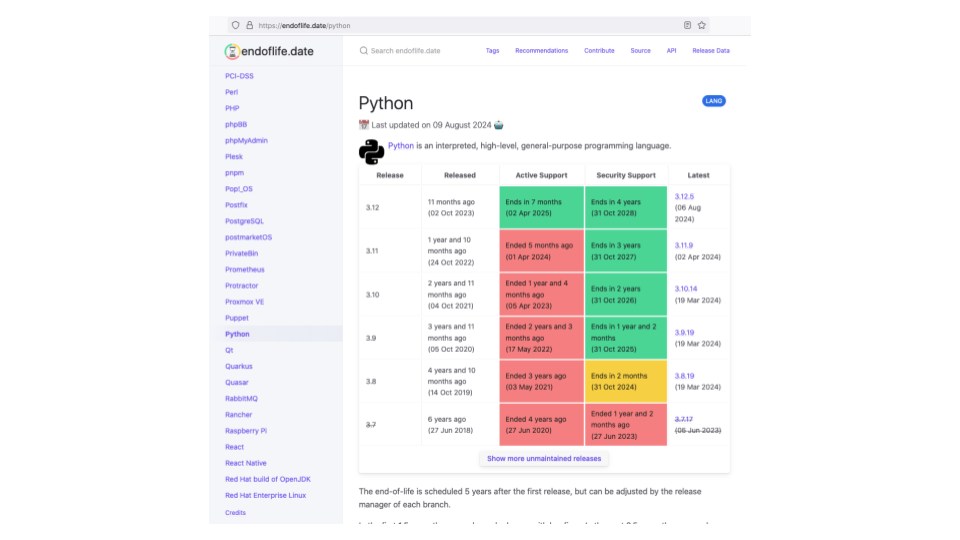

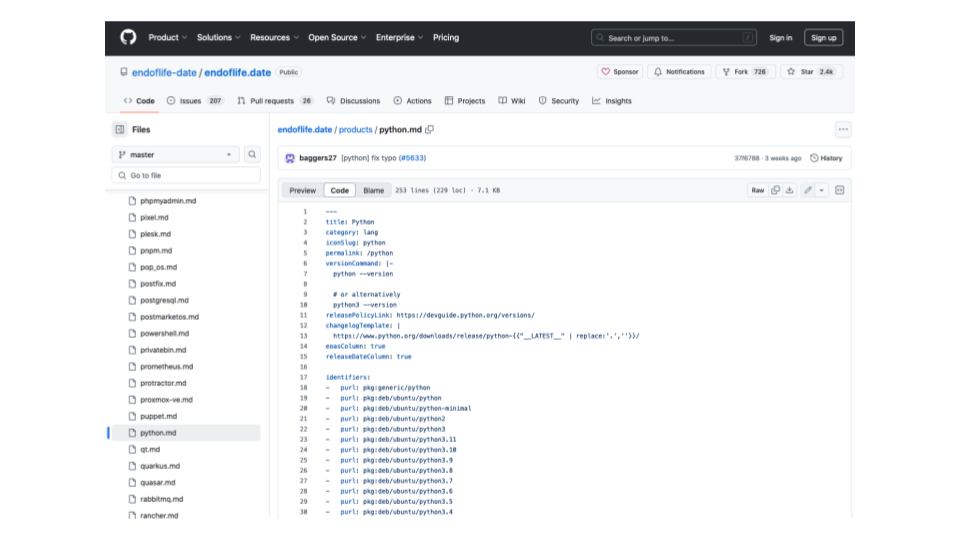

Endoflife.date is a website that lists the dates support for different versions of software packages ends, in a consistent interface. It's great for quickly looking up dates at an easily known URL.

They track over 5000 releases from over 300 products.

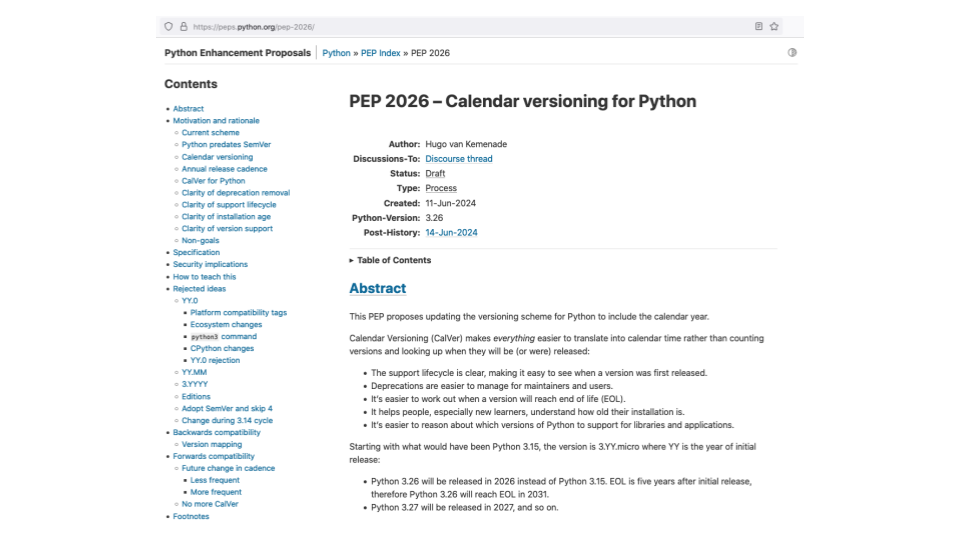

BTW do you know Python is thinking of moving to calendar versioning? So the next version will be 3.25. This makes it easy to work out which year support for this version ends.

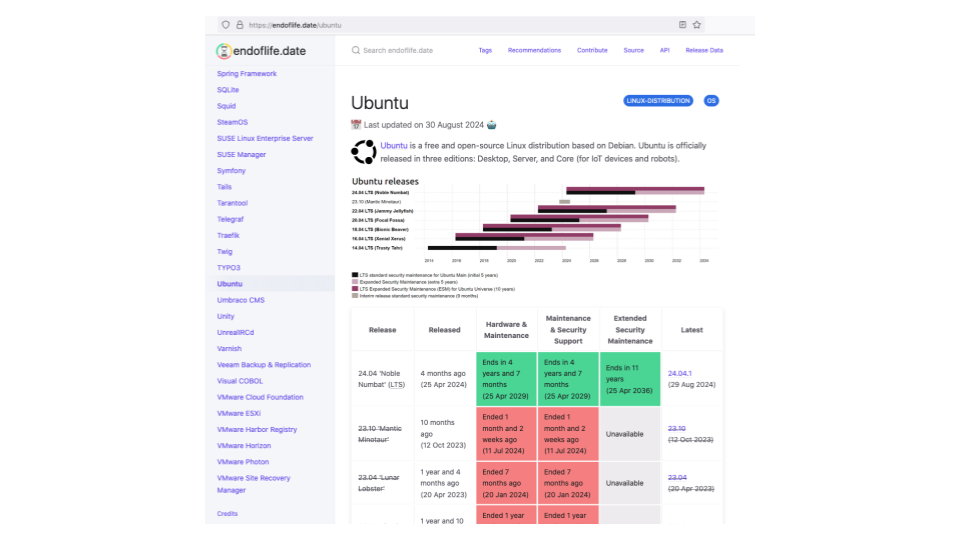

Ubuntu has been on calendar versioning for a while, but personally I still find it easier to look up dates here.

Also, this website is great for looking up which codename is for which version. I never bothered to memorize them and this way when someone says "Are you using Ubuntu Zonky Zebra?" I can just look up what number that means here.

Open Data Scotland lists open data sets from across Scotland.

It has information about over 2000 data sets and the different formats each is available in.

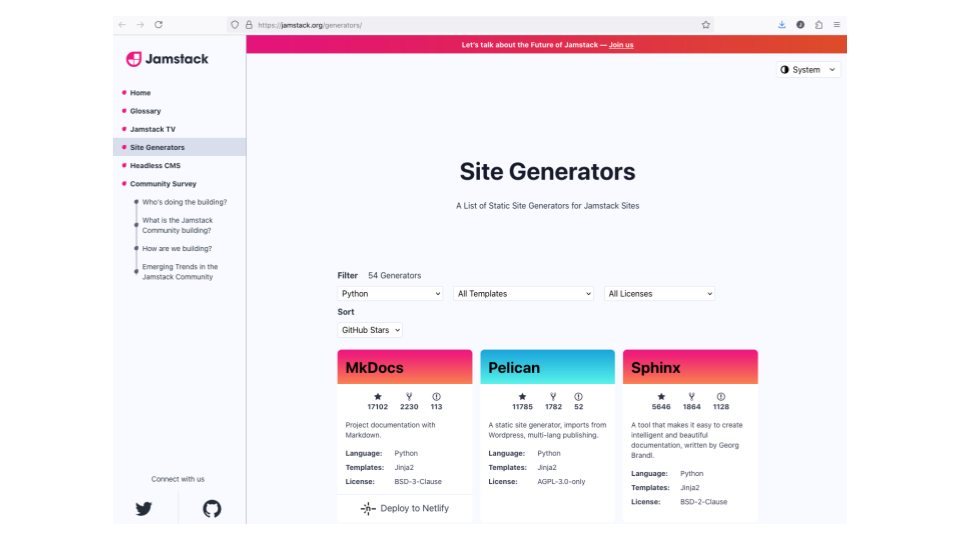

Jam stack lists static website generators - 55 written in Python.

Why am I showing you these websites? They all crowdsource their data in Git repositories.

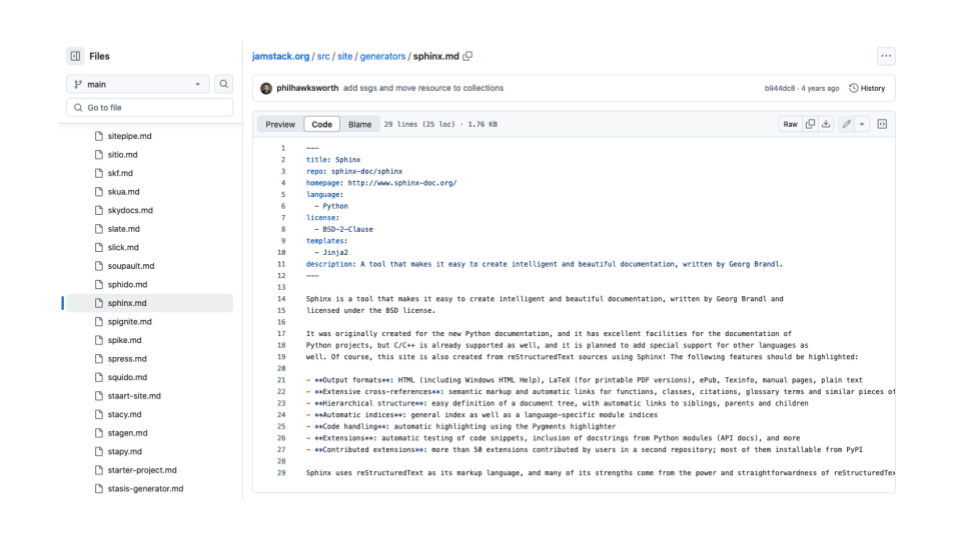

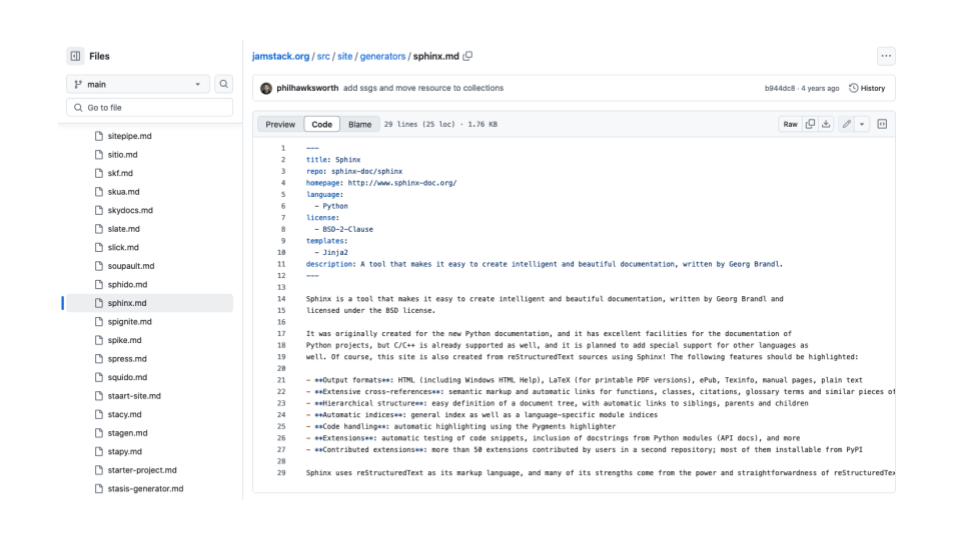

Here's the jam stack repository. You can see each product has one file, and each file has markdown content about that product. The YAML block at the top contains information such as the programming language.

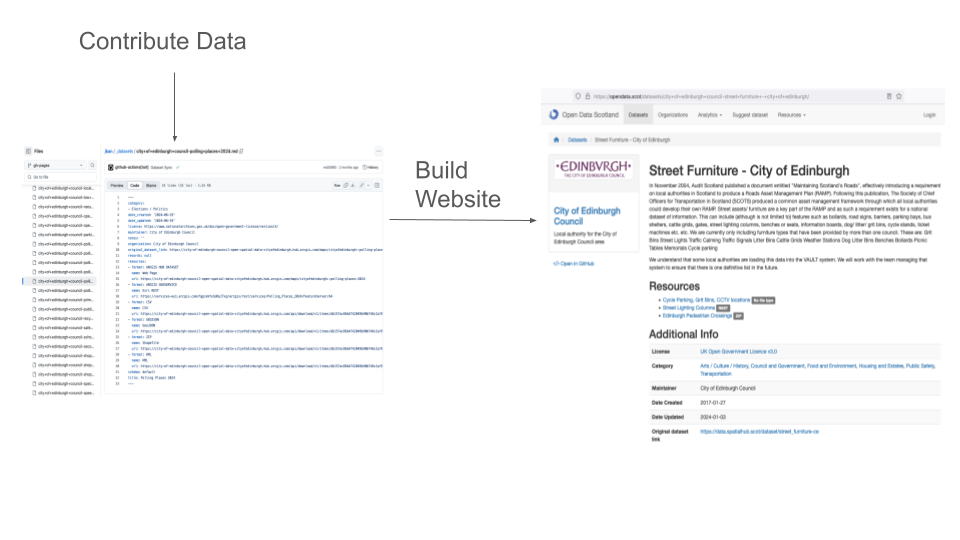

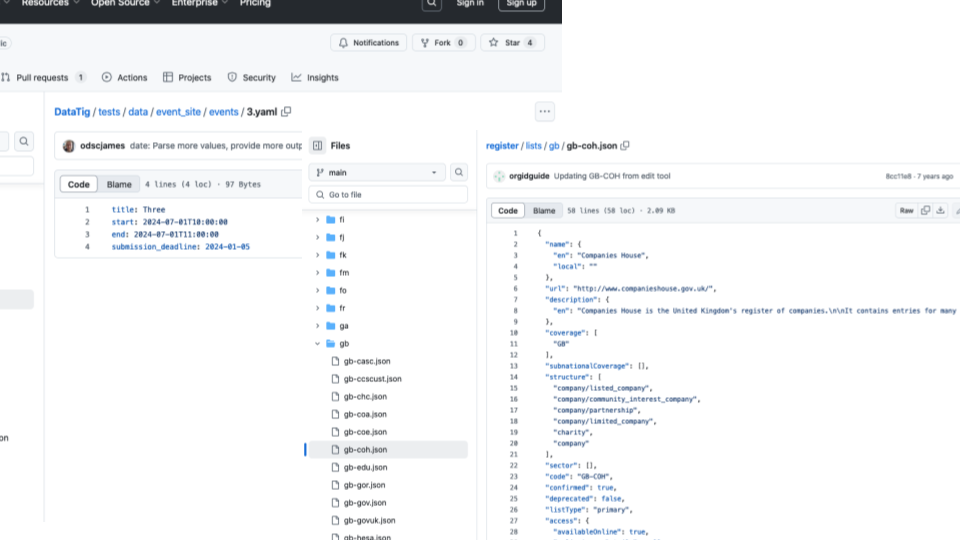

This is the repository for Open Data Scotland. A file for each data set and the YAML block lists the different formats.

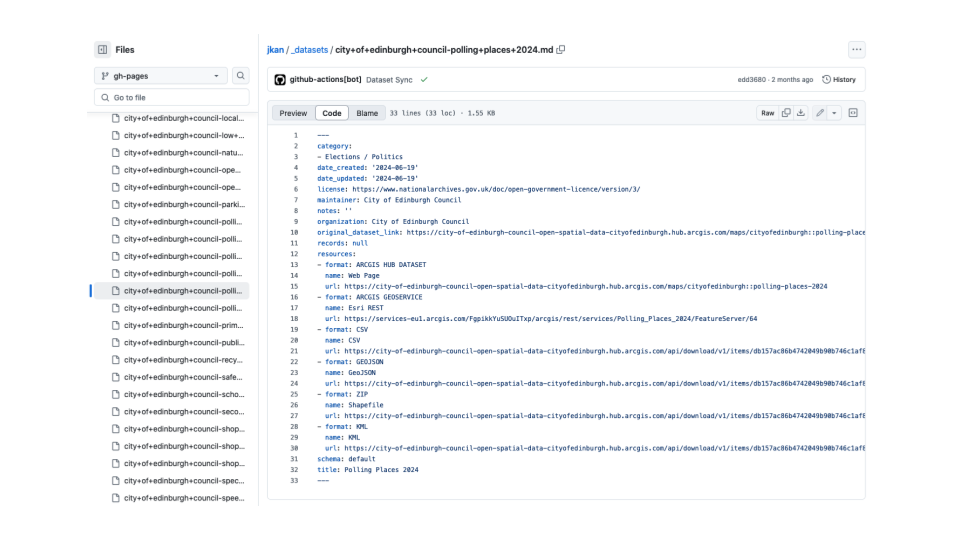

This is the repository for endoflife website.

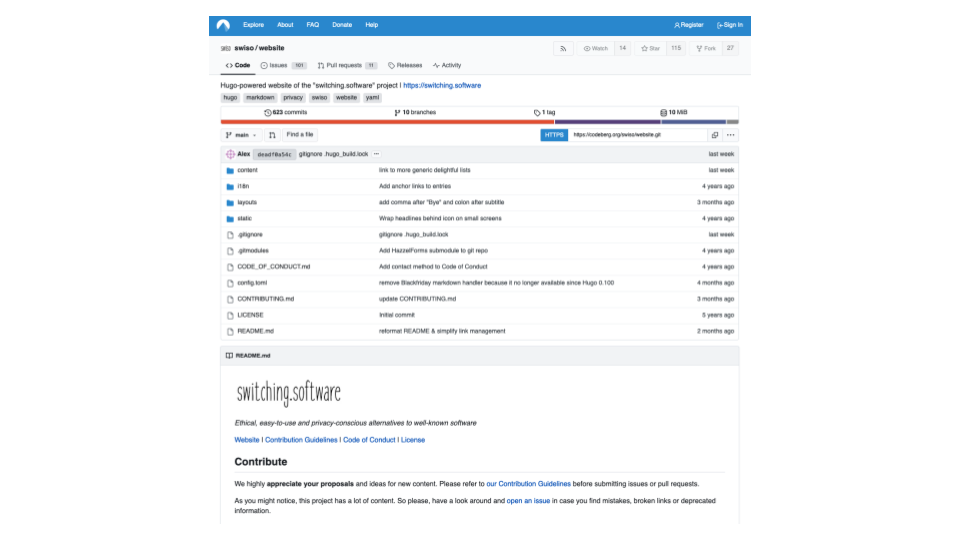

By the way, there will be a lot of GitHub screenshots because GitHub is the most popular git host. But other Git hosts are available and most of the things I will say apply to all Git hosts. This is a project hosted on Codeberg.

So basically what's happening here is people are contributing data into a Git repository, and from this they then publish a static website.

Is this a good idea?

Pros:

Good safe storage and hosting of data - Git has been around for years and is rock solid.

History - you get a history of the data for free.

Data in a kinda open format for reuse - the data is just in files and there are many ways to process it.

Lots of tools for building a nice static website with the data - I just showed you a list of 361 tools.

People can contribute with PR's, an approvals processs & diffs - and they already know how to use Git.

Have one file per record for easy Git merges with few Git conflicts (more on this later).

Lots of no money hosting options with no sysadmin work - you can host a public repository on GitHub for free and use Actions to host a website on Pages for free. No sysadmin worries or pager duties either.

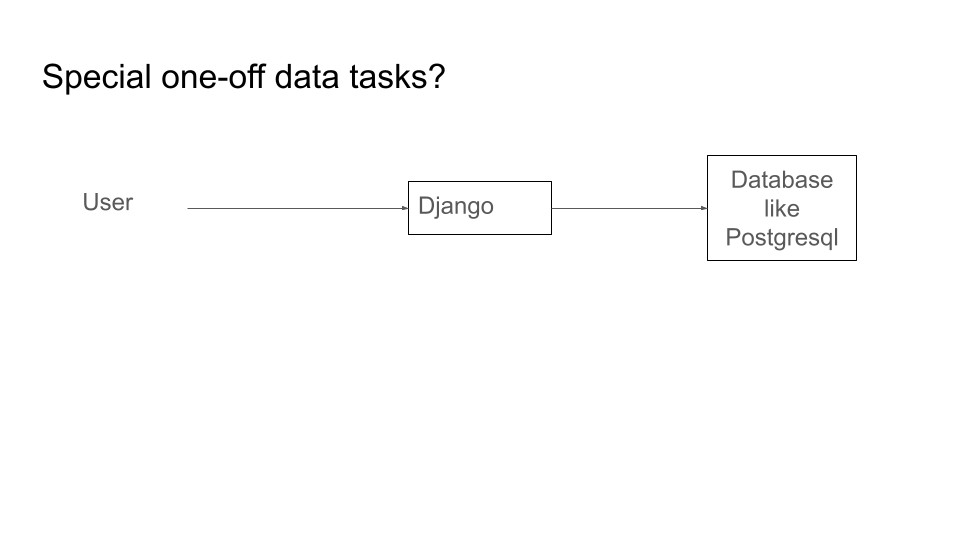

Another advantage is special one-off data tasks.

With a traditional web app their may be problems. Your app may be set up nicely to allow editing one record at a time.

But what happens if someone comes along and says they need to add a record for most countries - 250 records - at once? There may be no nice way to do this and it may be difficult.

This was a real request on one of our projects.

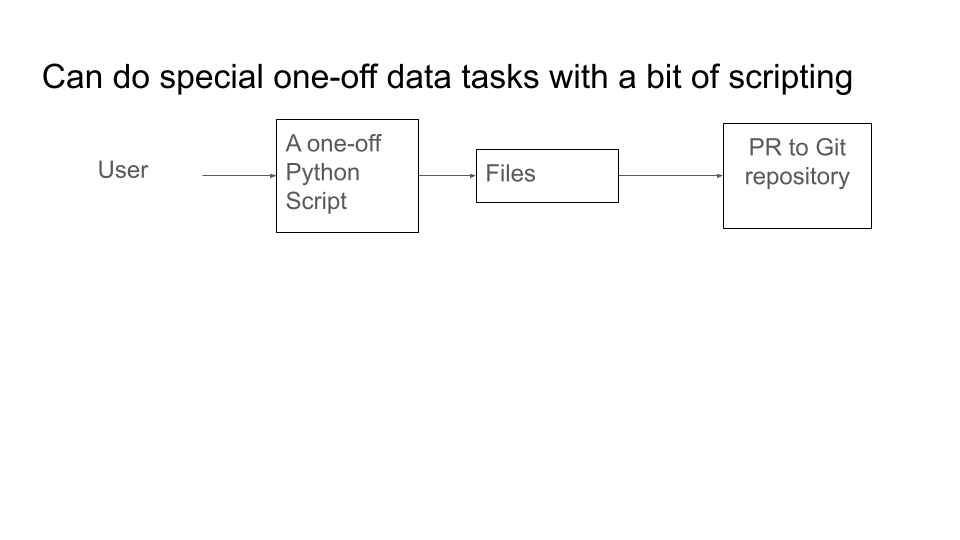

With a Git repository, if the existing tools don't support it that's not a problem. The person can write a one off script to generate the files and they can all be put in one PR to be checked.

Cons:

History can be a con as well as a pro. Some projects might have the requirement that data can be fully deleted from them on request, including from the history. While rewriting history is possible in Git, it's not easy.

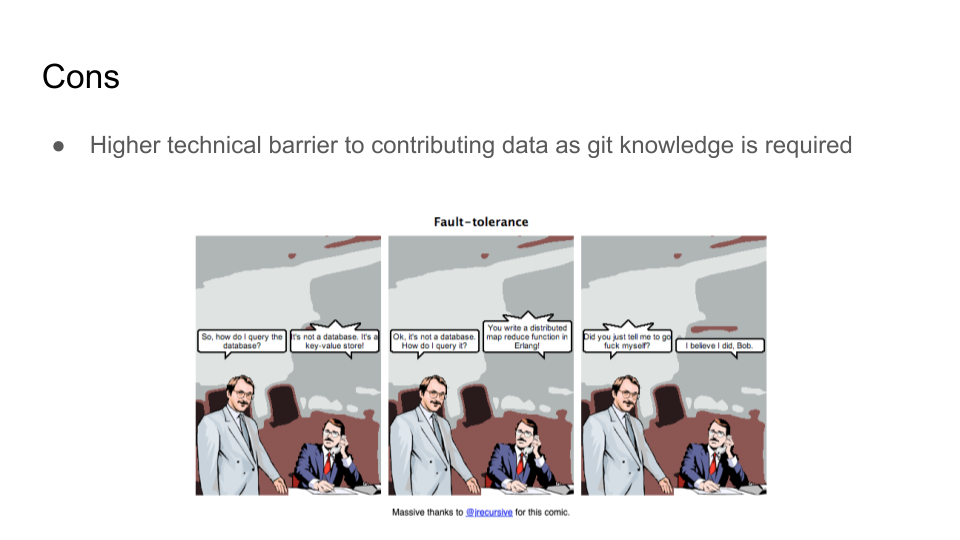

And one really big disadvantage ...

Earlier I said people are familiar with Git, but that's not true. Only computer programmers use it, and some of them don't like it. This creates a high technical barrier to contributing data and gives me a chance to bring out one of my favorite comics about tech accessibility:

Bob: So how do I query the database?

Jim: It's not a database. It's a key-value store!

Bob: Ok, It's not a database. How do I query it?

Jim: You write a distributed map reduce function in Erlang!

Bob: Did you just tell me to go f*** myself?

Jim: I believe I did, Bob.

I ran Open Tech Calendar, listing tech events around the UK for years.

At one point someone suggested to me that it should just be a repository of iCal files that people could edit by hand. (iCal files are the standard for calendar data.)

So firstly that's a barrier to contributing as Git knowledge is required. Instead we had a nice form on our website and many non-programmers contributed events over the years.

Secondly that's a barrier to contributing data as the iCal format is really annoying to edit by hand! Would you enjoy hand editing this? Do you think you could get it right first go?!

I like to think part of the success of Open Tech Calendar was that I completely ignored that advice.

So should you use a Git repository to crowdsource data?

In some situations the technical barrier problem is fine as all the people contributing to the project are probably technical anyway (ie endoflife.date).

To try and reduce the technical barrier, many projects accept contributions via issues. However, this is still a barrier as people need to open an account on a website they are not familiar with and work out the new issue form - which is almost like a forum post but with extra weird options like "assigned to".

So is this a good idea?

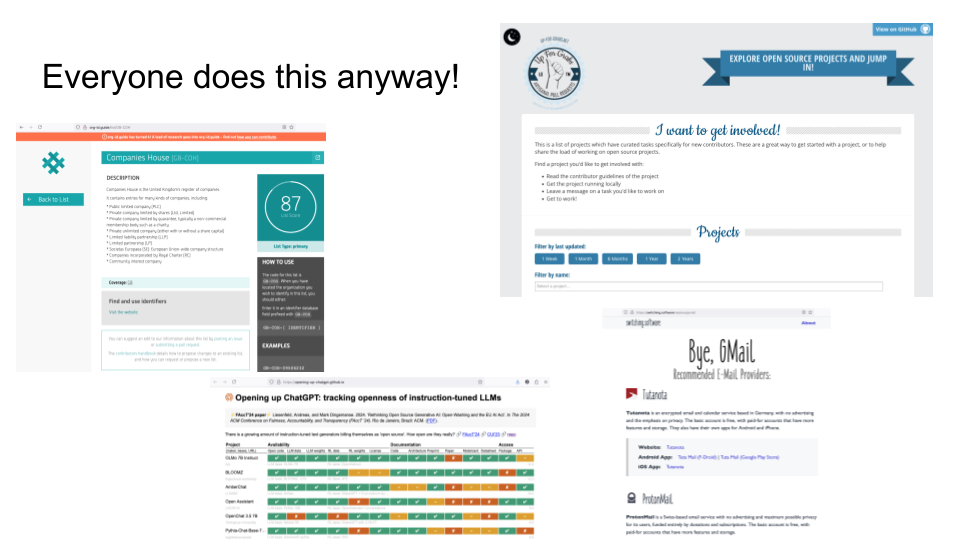

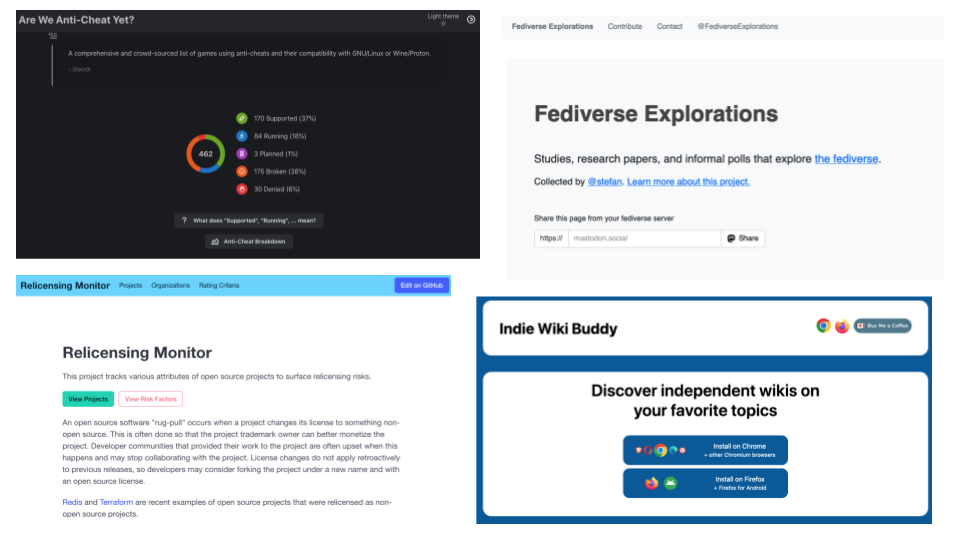

Well ... everyone does this anyway!

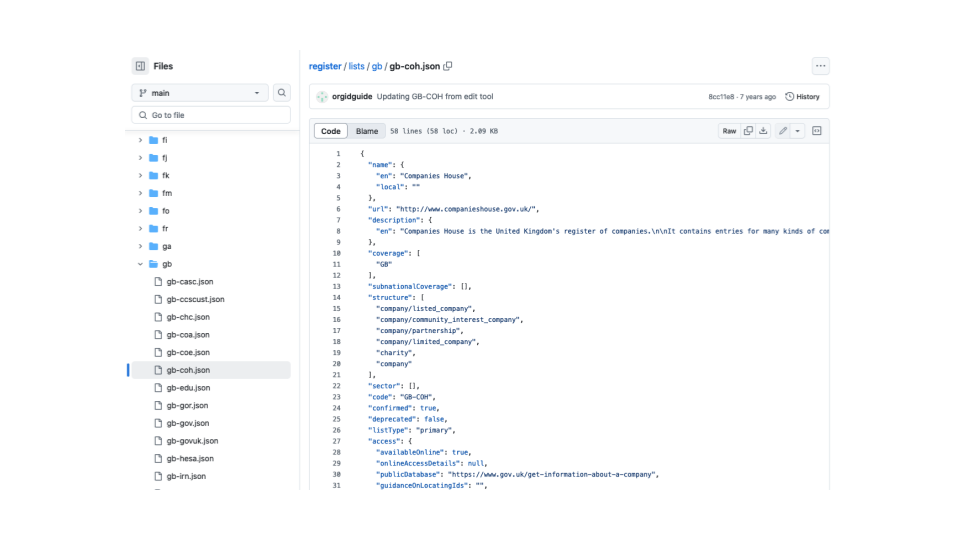

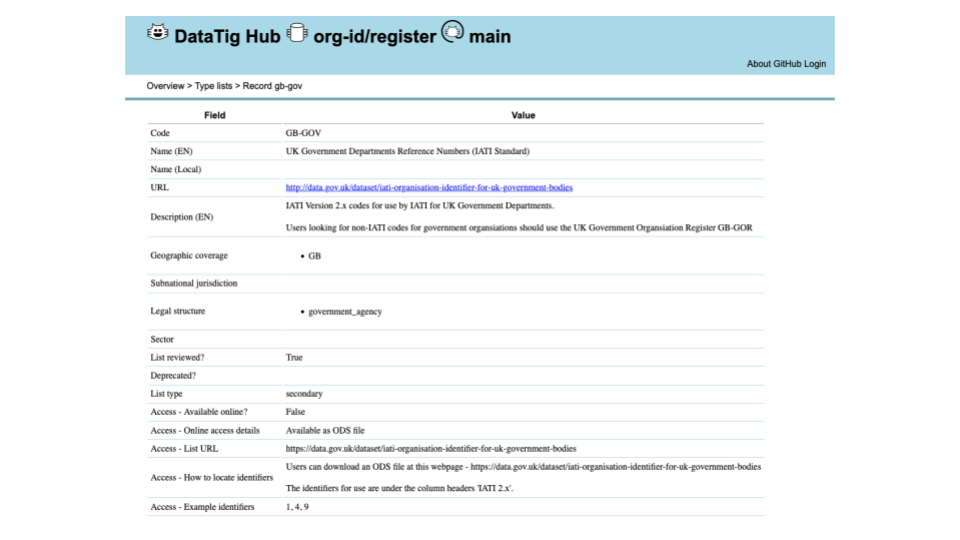

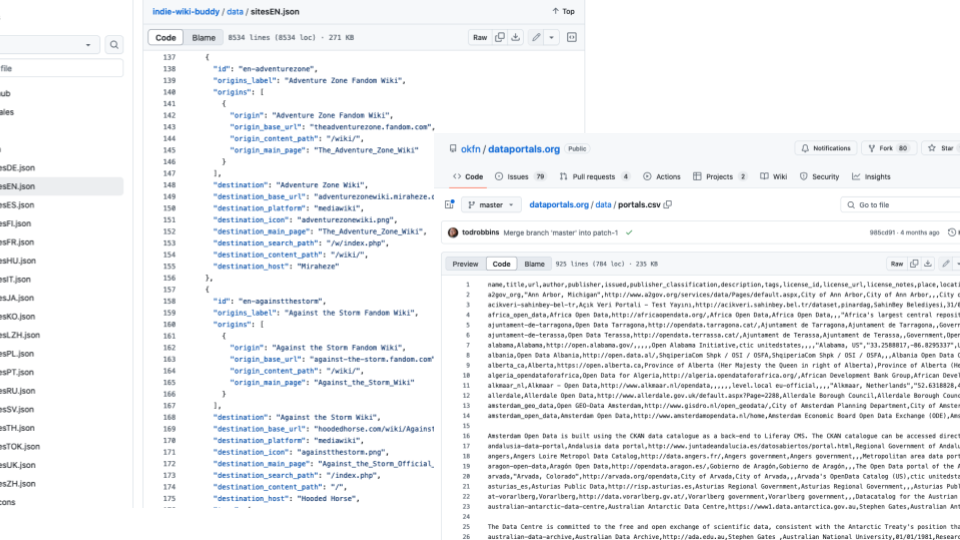

Org-id is a project we run at my work. It lists places that list companies. To explain why this is important to our work isn't relevant now and would take too long (but this blog post explains if you are interested).

Up for grabs lists projects with issues marked as suitable for newcomers, to encourage people into open source.

This website lists LLM engines and how open they are, by various criteria.

Switching software lists alternatives to proprietary programs.

I could go on - but you get the point.

Problem / Opportunity: Everyone reinvents the wheel!

Some static site generators are very popular, but everyone tends to reinvent the wheel when it comes to data tools and workflows.

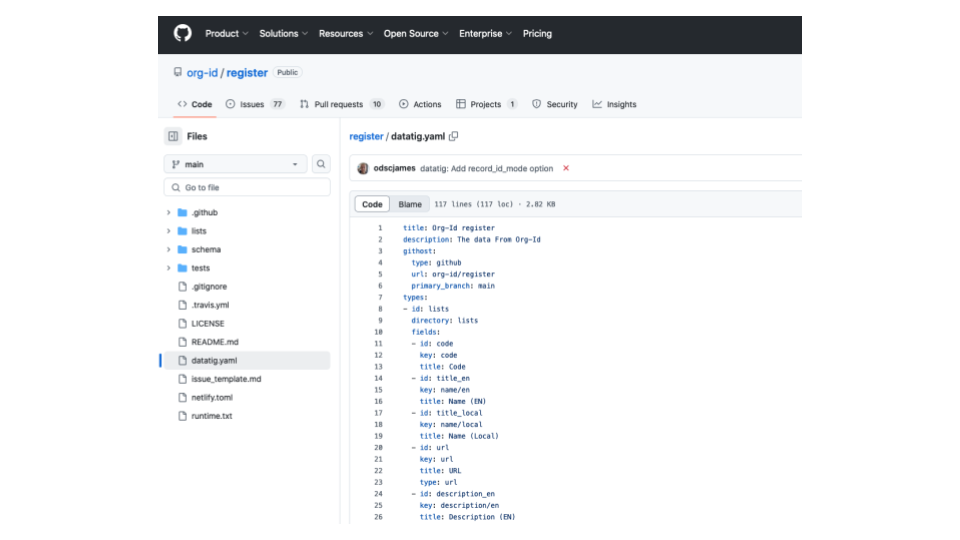

So this explains our project, DataTig.

It's for when a community of people want to crowdsource a data set and they use a Git repository to store the data.

- Lots of people do this & reinvent wheel each time they do

- Can shared tools help these projects?

- Help people get and reuse data

- Help people check data

- Help people contribute data

- (All Open Source)

So if you have a repository with data in it ...

You add a config file. This mainly describes the format of the data and the fields in it.

DataTig can then give you lots of advantages.

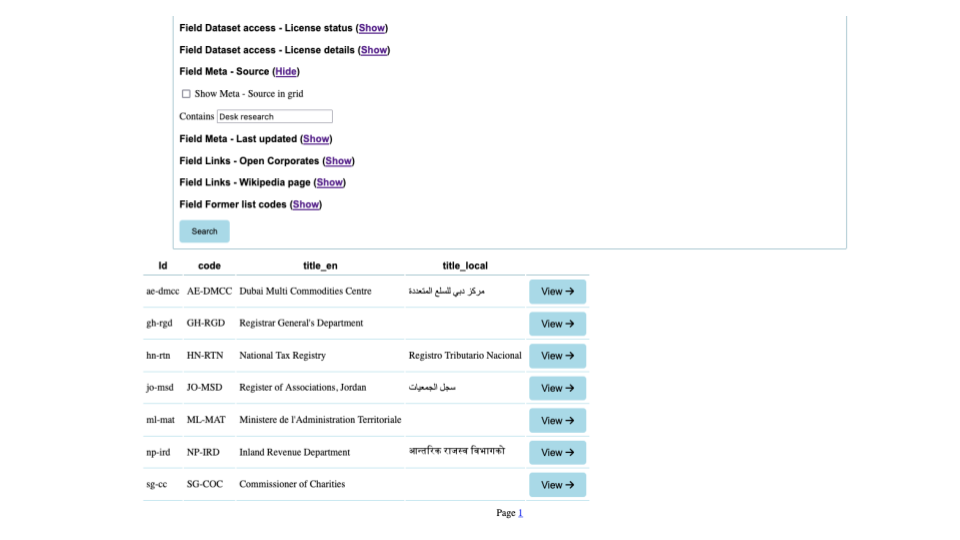

A search and filter UI to find records.

See the details of any records

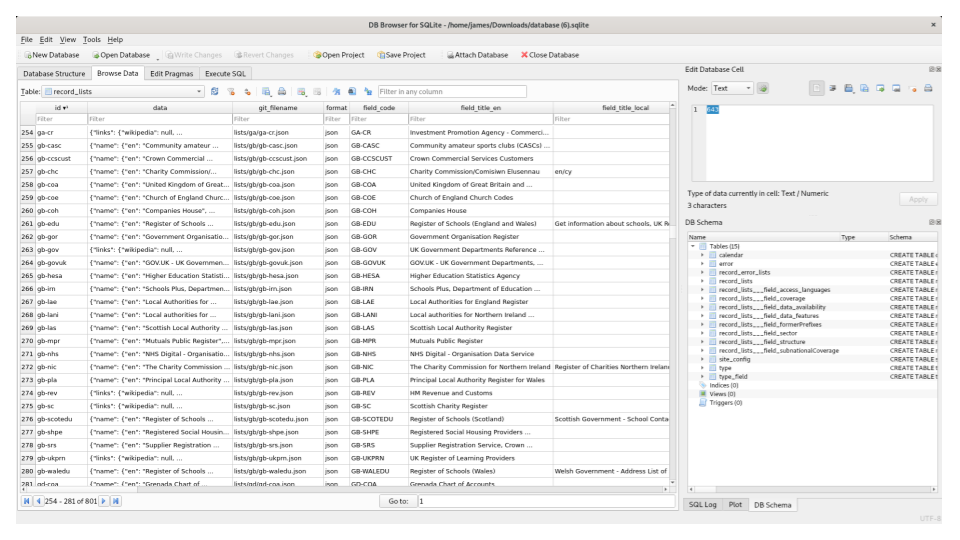

For reusing the data, you can export it all as a SQLite file and run custom queries against it.

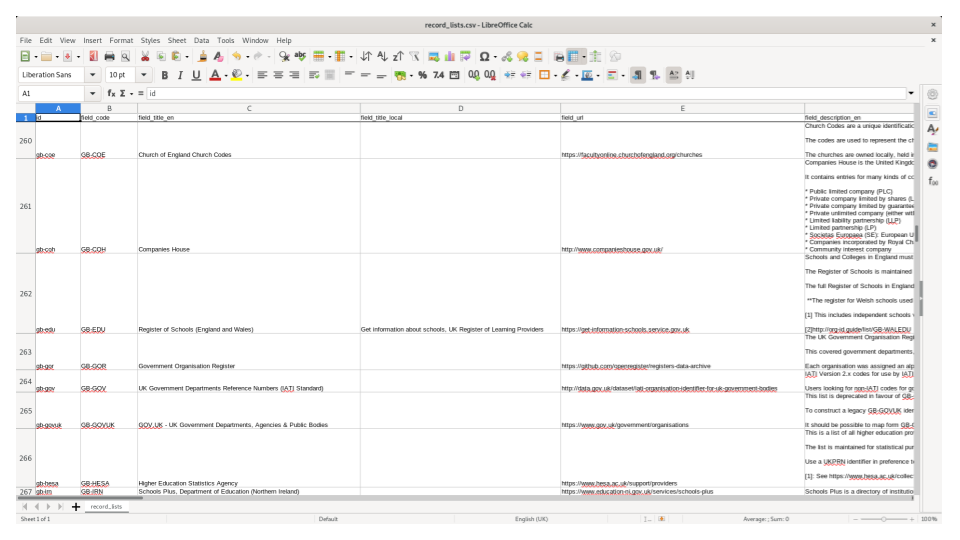

You can export it as spreadsheets in Frictionless Data format.

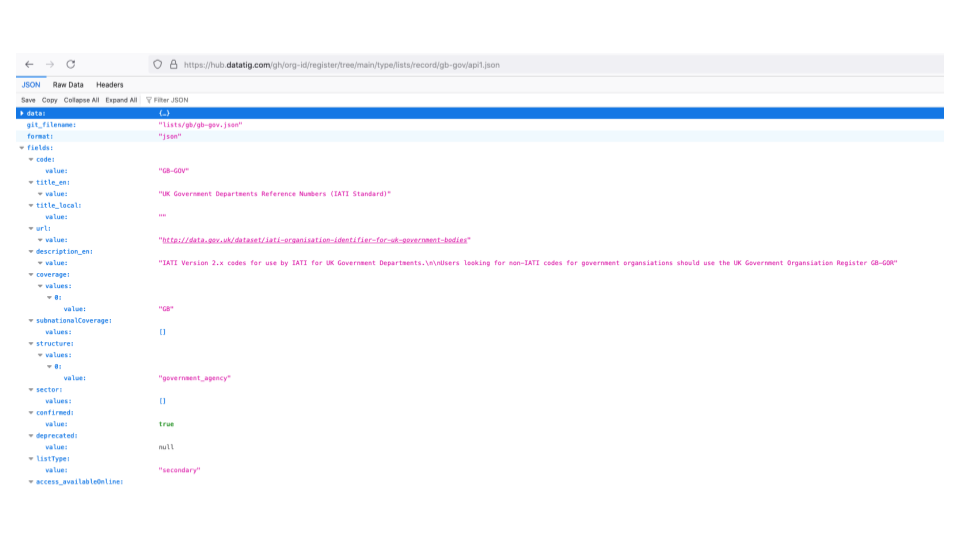

There's a JSON API for other apps to use.

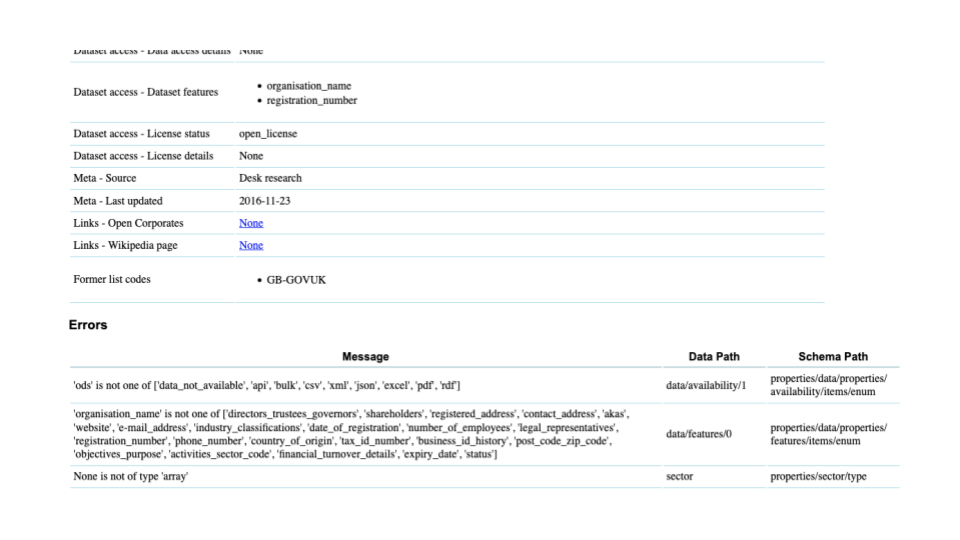

For helping the quality of the data it can check for errors and highlight them for you.

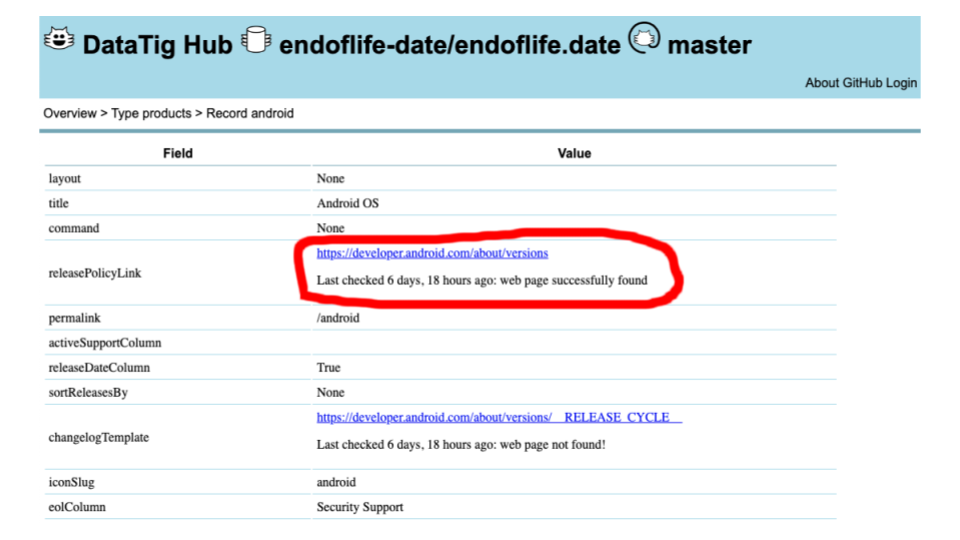

We can check that any links in the data are valid.

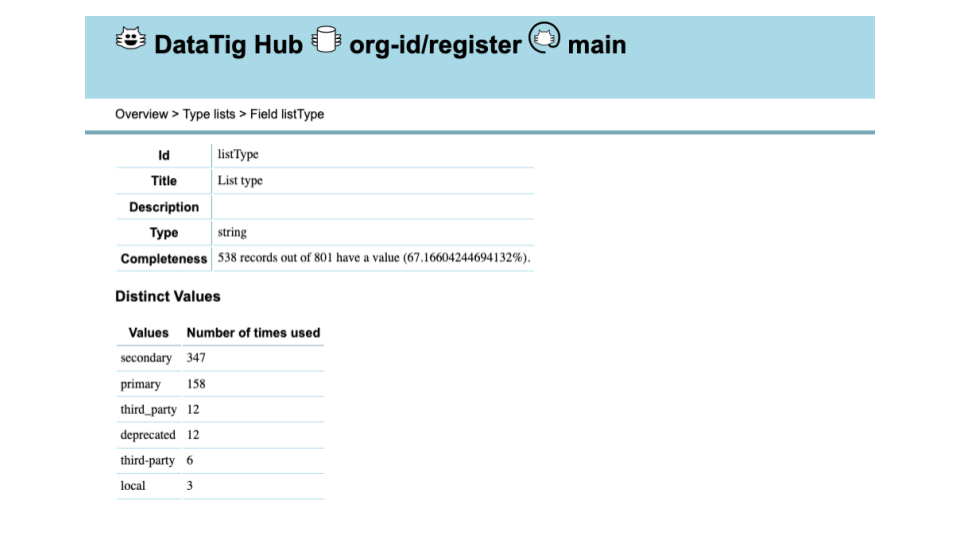

We can show you information about the fields.

Here you can see some tags use underscores and some dashes (third_party vs third-party) - this project should standardise on one.

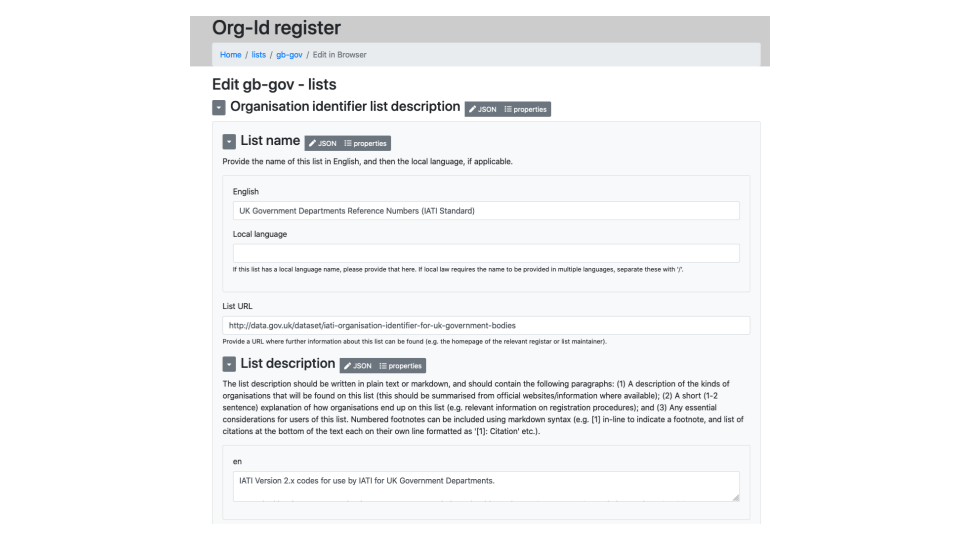

For people contributing data, we can make web forms.

This way we hope to try and make it easier for people and overcome the technical barriers to contributing.

For Markdown files, this can include a nice editor for the Markdown body and the YAML tags at the top.

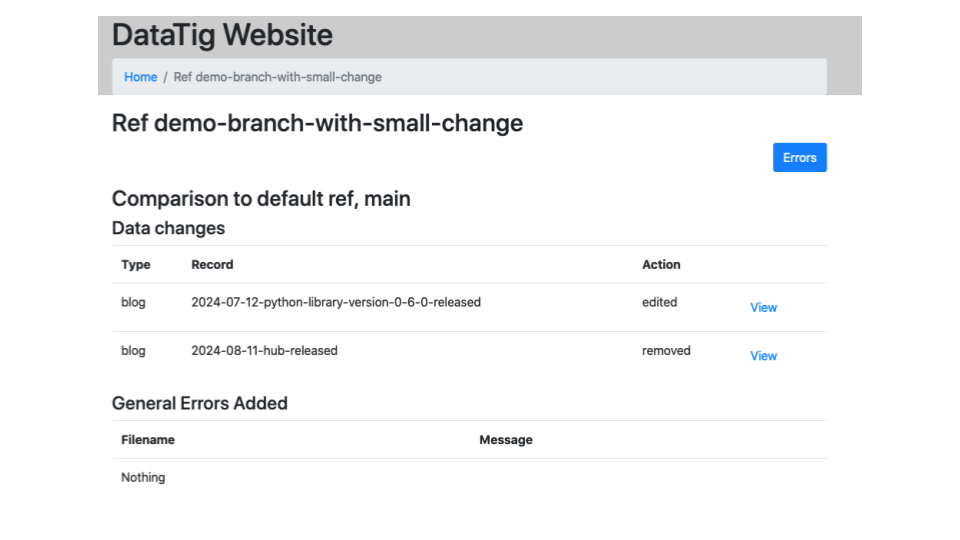

This is an experimental UI, showing the differences in data between a branch and the main branch. We think this will be useful attached to PR requests.

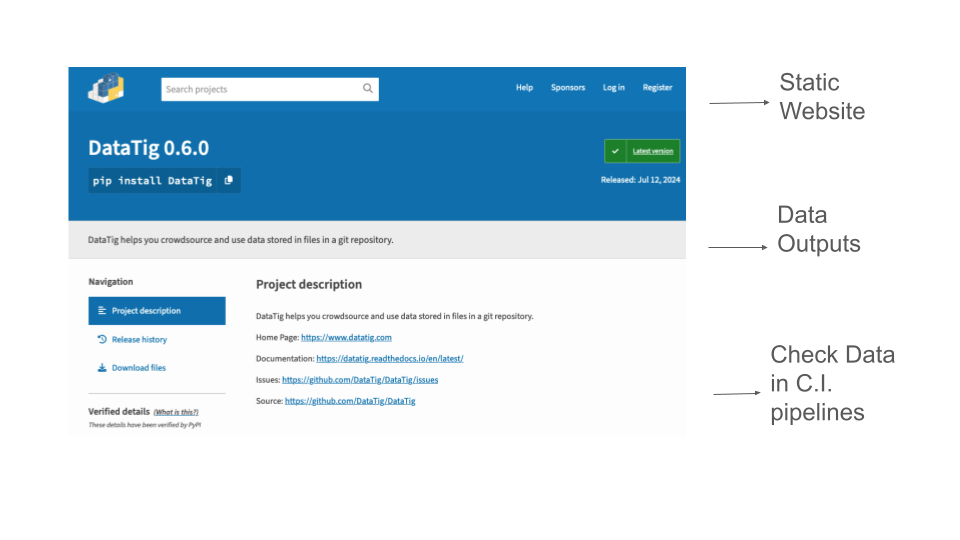

Ways to use this.

You can use it as a Python library. It can produce a static website, or the SQLite or spreadsheet exports you saw earlier.

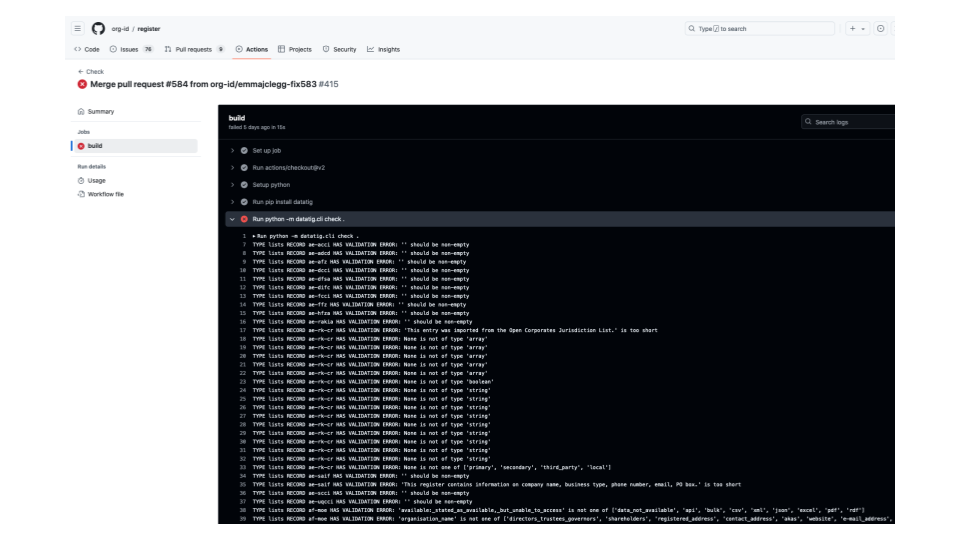

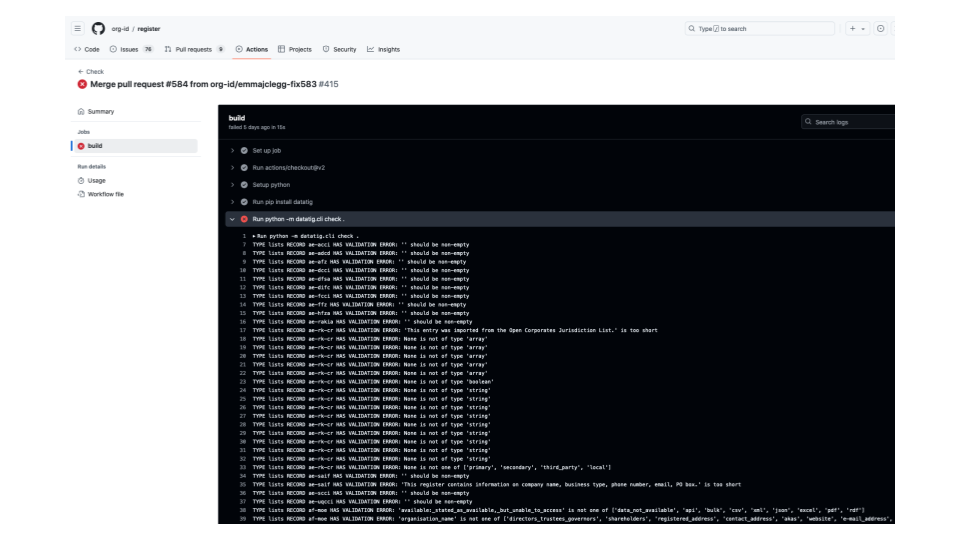

It can also be used in C.I. pipelines to check the quality of data.

Every time you push up a commit to GitHub, you can have it run tests and report any problems in the data.

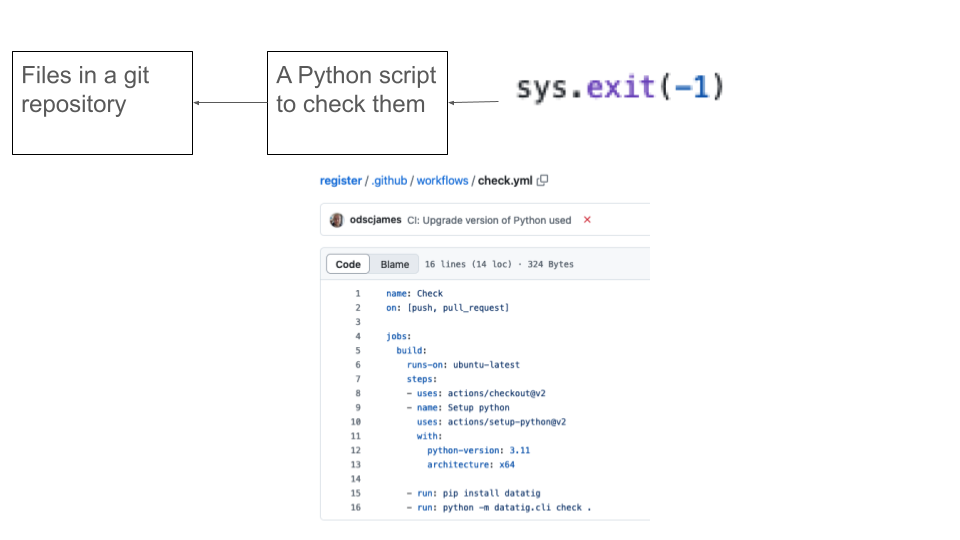

This is really easy to do in Python. If you have files in a Git repository, you can write a Python script to check them. It can be anything you can check in Python.

For example, if you have images you can check they are a minimum size.

If the script finds no problems, it exits normally.

But if the script finds problems, it exits by calling sys.exit(-1). (An appropriate import statement is needed too )

Then you just need a really simple GitHub Action config file.

- Check out the repository

- Install python

- Install your python script from wherever it is

- Run your python script.

That's it!

(We have docs on this.)

You'll now get a check every time a commit is pushed up.

You can require these to pass before people are allowed to merge PRs.

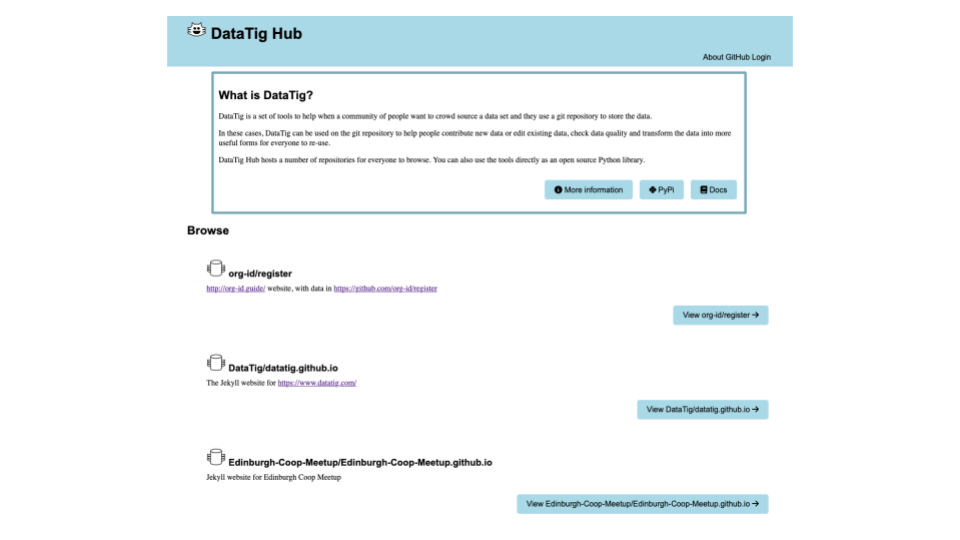

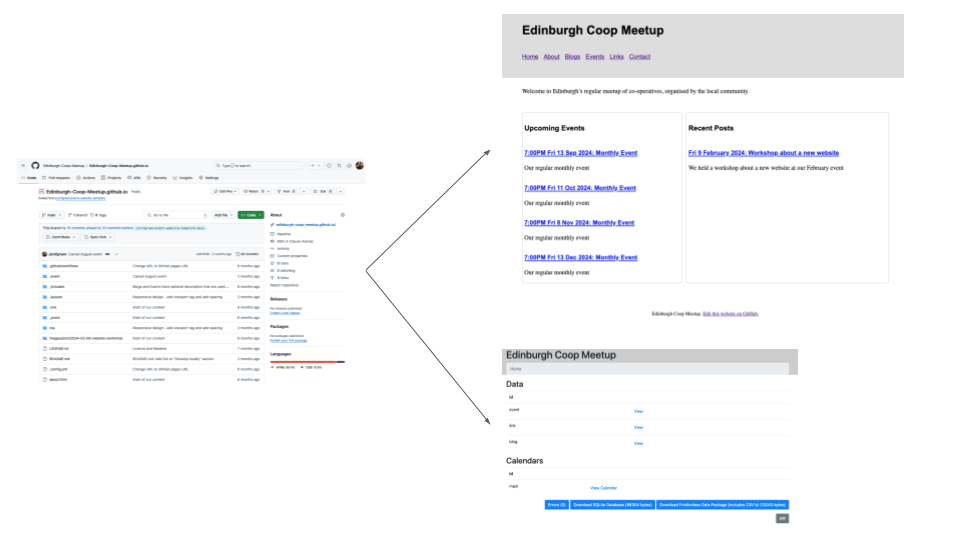

We also have our Hub web application available. This is a Django application that uses the Python Library and can host multiple repositories and multiple branches.

If you log in with GitHub you can fill out a form, and sometimes it will try to make the commits in a new branch in GitHub for you. This hopefully reduces the technical barrier to contributing.

It does a few other things you can't do in a static website, but these days you can do so much with a static website and client side JavaScript and WASM in the web browser.

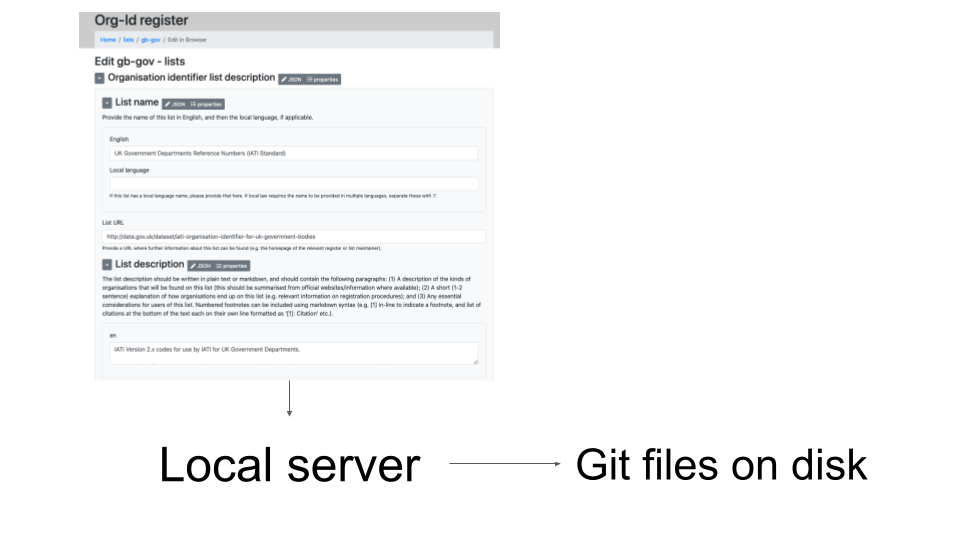

There is also an experimental local server which you can run directly in your machine. When you fill out a form in your web browser, it will save the data on your disk for you to commit as normal.

Is this also a barrier to entry? Some of these screens are very data heavy.

But you can use as much or as little of this as you want.

You can use GitHub Actions to do one build from one repository and create both a custom static website with you own messaging and a DataTig static website in a subdirectory for data users and contributors.

(We have docs on this.)

How to store the data in the git repository?

One way of storing data is a separate file for each record and a YAML block and a markdown body. This is a pretty good way to organise the data in the repository.

You can also just have YAML or JSON files. We think JSON files are harder to read and hand edit, and the trailing slashes makes for messier diffs.

But the main thing to avoid is putting many records in one file. We've often seen one JSON file with a big list.

This causes problems because as many people edit different records at the same time, the chances of messy merges and maybe even merge conflicts increases. The history gets messier too.

We've sometimes seen a CSV file. This is hard to edit and operations like adding a field are harder to do.

So that's our project.

But other ways of running community data projects are available, and we've given you one big reason why you might not want to use Git.

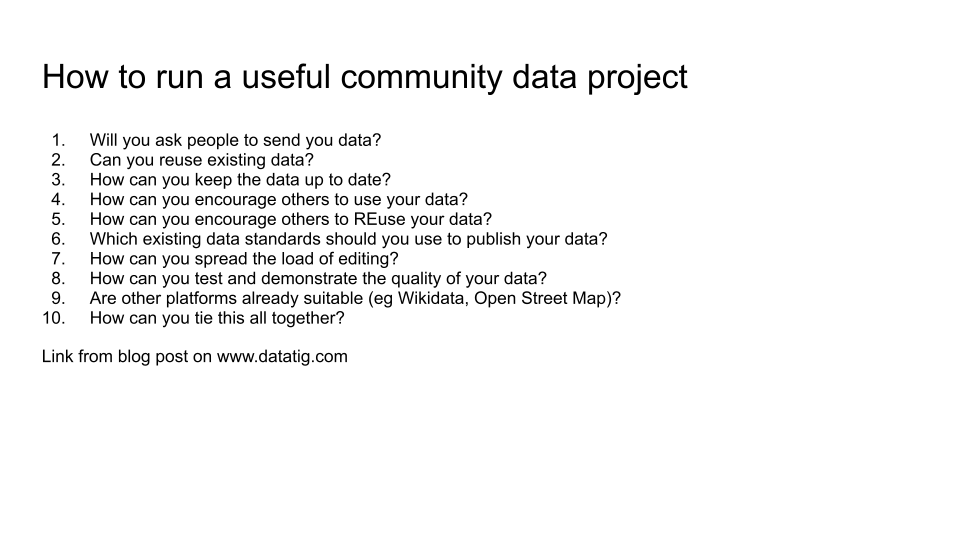

However you choose to run your project, we think it's important to think about the data aspects of it.

- Will you ask people to send you data?

- Can you reuse existing data?

- How can you keep the data up to date?

- How can you encourage others to use your data?

- How can you encourage others to REuse your data?

- Which existing data standards should you use to publish your data?

- How can you spread the load of editing?

- How can you test and demonstrate the quality of your data?

- Are other platforms already suitable (eg Wikidata, Open Street Map)?

- How can you tie this all together?

We wrote this blog post that goes into that more.

Thank you!

DataTig

DataTig